Five years of GPT progress

If you want to read more of my writing, I have a Substack.

In this article, I discuss the generative pre-trained transformer (GPT) line of work, and how it has evolved over time. I focus on the SOTA models, and the differences between them. There are a bunch of different articles summarizing these papers, but nothing that I’m aware of that explicitly focuses on the differences between them.

I focus on the GPT line of research as that’s what’s driving the current fever pitch of development. There’s a ton of prior work before large GPTs (eg the n-gram models from the 2000s, BERT, etc) but this post is super long, so I’m gonna save those for future articles.

GPT

The first GPT paper is interesting to read in hindsight. It doesn’t appear like anything special and doesn’t follow any of the conventions that have developed. The dataset is described in terms of GB rather than tokens, and the number of parameters in the model isn’t explicitly stated. To a certain extent, I suspect that the paper was a side project at OpenAI and wasn’t viewed as particularly important; there’s only 4 authors, and I don’t remember it particularly standing out at the time.

The architecture is remarkably unchanged compared to GPT-3:

- Decoder-only transformer, with 12 layers, 768 embedding dimension, 12 attention heads, and 3072 (4x the embedding dimensions).

- They use Adam, with a warm up, and anneal to 0 using a cosine schedule.

- Initialize weights to N(0, 0.02), using BPE with a vocab of 40000 merges.

- Activations are GELUs.

- Context of 512

- 117M parameters

- Learned position embedding, not the sinusoidal ones from “Attention is all you need”.

The number of parameters isn’t explicitly discussed, but appears to be roughly 120M, easily enough to fit on a single V100 or a standard consumer GPU (rough estimate of 120M parameters for the model, 240M for the optimizer, for 360M parameters; assuming each is a float32, then this takes up 4 bytes * 360M = 1440MB/1.4GB.

They use the BooksCorpus dataset (~20M tokens), training for 100 epochs with a batch size of 64. 20M tokens is a very small dataset by modern standards, as is a batch size of 64.

The most surprising thing compared to modern GPTs is that they train for 100 epochs. Modern GPTs rarely ever see repeated data, and if they do, they typically only see certain datapoints a small number of times (2-4x), and the entire dataset is never repeated 100x.

GPT-2

GPT-2 is where the language models start to get big. This is the first time that OpenAI trains a model with >1B parameters. We start to see scale as a primary concern; in GPT, the authors trained a single model, but here, the authors train a range of models, with sizes ranging from GPT to 10x GPT (which is the actual GPT-2 model).

The differences in architecture compared to GPT are as follows:

- They layernorm the inputs and add an additional layernorm to the output of the final self-attention block

- Weights are scaled by layer by 1/sqrt(n)

- Vocabulary of ~50k (up from ~40k)

- Context of 1024 (up from 512)

- Batches of 512 (up from 64)

- Largest model is 1.5B parameters

The dataset is much, much bigger, going from roughly 20M tokens (4GB) of data consisting of publicly available books, to 9B tokens1 (40GB) of text scraped from the internet (WebText).

It’s unclear if they trained the model for 100 epochs as before; they say they followed the same training procedure, so presumably they did. Again, this is a significant departure from later work.

Nothing here is particularly different from GPT; most of the changes are related to making the model bigger. The only other changes are the layernorm changes and the weight scaling, which don’t seem to make a big difference (although, as always, more ablations would be nice).

GPT-3

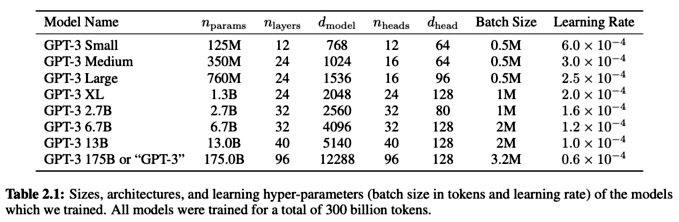

Here is where the era of truly large language models began, and the current AI bubble excitement took off. In the paper, the authors train 10 models, varying from 125M parameters (”GPT-3 Small”) to 175B parameters (”GPT-3”).

For each of the models, the architectures are identical to GPT-2 with the exception that they use “alternating dense and locally banded sparse attention patterns in the layers of the transformer.” The sparse attention here refers to the attention mechanism introduced in the Sparse Transformer, which lets attention scale proportional to \(O(n \sqrt{n})\) (where \(n\) is the context length). The standard dot-product attention mechanism scales proportional to \(O(n^2)\), so this is a substantial gain. I would have loved a proper ablation to see what difference sparse vs dense attention makes, but alas.

I’m very curious why they used sparse attention. Reproductions and later papers uniquely use dense attention. As this paper came before FlashAttention and some of the other algorithmic innovations that make dense attention faster, maybe this was a computational bottleneck? It’s really unclear.

They don’t provide any detail about the computational architecture, i.e. how they distributed the model. The authors claim it’s because it doesn’t really matter, but I think it was restricted for competitive reasons, as it makes the paper much more difficult to reproduce. Megatron, which I’ll discuss later, was highly influential because they went into detail about how they made model parallelism work for their GPT.

What I find really interesting about the GPT-3 paper is that it was an incredible advance without a lot of novelty. They took their existing methods and “just” scaled it up! Because of the need for novelty, there are many research projects that don’t get pursued because they’re “only” engineering projects, or they “only” do hyper-parameter tuning and wouldn’t be able to get published, even if they had impressive performance improvements. That OpenAI went against the grain here is a credit to them (and they were rewarded, with GPT-3 getting a best paper reward at NeurIPS ‘20).

This is particularly problematic because we know that adding complexity to our models increases performance (see: R^2 vs adjusted R^2 for simple linear models). Because of the need for novelty, there are many research projects that don’t get pursued because they’re “only” engineering projects, or they “only” do hyper-parameter tuning and wouldn’t be able to get published, even if they had impressive performance improvements. That OpenAI went against the grain here is a credit to them.

This is a strength of OpenAI (and Stability.ai, Midjourney, basically everywhere that’s not FAIR/Google Brain/Deepmind/etc). You could alternatively frame it as a weakness of the more academic labs that have promotion/performance review policies driven by publications.

Jurassic-1

I wasn’t sure whether or not to include Jurassic-1. It’s a model from the Israeli tech company AI21 Labs. I haven’t heard a lot about them, but the paper’s cited by a bunch of the papers later on in the article; they trained a 178B parameter model that outperformed GPT-3 in a few categories, and was faster for inference. It’s impressive that they’re competing with DeepMind, OpenAI, Nvidia, etc. despite only having raised <$$10M at the time. They made a zero-shot and few-shot test suite publicly available.

Like many other papers, they don’t go into detail about the engineering details behind training a large model (178B parameters) over 800 GPUs:

The paper is remarkably sparse on details, which I suspect was done for competitive reasons, just like GPT-4.

Facebook is the only company to go into detail about their experiences training a 175B parameter model, just like Nvidia is the only company to go into detail about the computational architecture required to train a LLM over many GPUs (see: the Megatron paper, next). In both cases, the companies are commoditizing their complements and strengthening their main lines of business by making it easier to train large models.

Jurassic uses a different architecture from GPT-3, but again, doesn’t go into much detail:

- 76 layers (vs 96 layers for GPT-3)

- They use the SentencePiece tokenizer, with a large vocabulary of 256K (vs GPT-3 which used BPE w/ ~50k tokens).

Neither of these changes are material, in my opinion. I think what we’re seeing is that there’s a relatively large degree of freedom in model architectures which produce similar results. This is borne out by their evaluation, which has results similar to GPT-3 (better in some categories, worse in others), although Jurassic-1 is faster for inference due to being shallower.

We’re starting to see a consistent pattern emerge:

- Papers introduce a bunch of changes, their own dataset, and have a new SOTA

- but they don’t do a proper ablation, so it’s tough to understand what was important and what drove the improvements

GPT-2, GPT-3, Jurassic-1, etc. all did this.

Megatron-Turing NLG

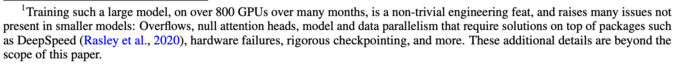

Megatron was a highly influential paper that introduced efficient model-parallel architectures. If you’re interviewing for a LLM job today, you’re going to be expected to be familiar with it. Megatron introduced tensor parallelism, a variant of model parallelism that splits the models to allow for intra-layer model parallelism, achieving 76% as efficient as a single GPU baseline (although the baseline is only 30% of peak FLOPS).

Prior to megatron, the published SOTA for model parallelism was to use model pipelining, e.g. GPipe. However, this was difficult to do and not well supported by code. There were attempts to support tensor parallelism, e.g. Mesh-Tensorflow, which introduced a language for specifying a general class of distributed computations in TensorFlow, but nothing had really dominated. Interestingly, the first author had just left DeepMind 1 year before this was published, so this was possibly his first project at Nvidia.

Megatron has the realization that, if you have a neural network like this:

\[Y = f(XW)\]and you split \(W = \begin{bmatrix} W_1 & W_2 \end{bmatrix}\), i.e. along the columns, then \(Y = \begin{bmatrix}f(X W_1) & f(X W_2)\end{bmatrix}\), so you don’t need to do any synchronization to calculate \(Y\). Consequently, the only points where you need synchronization (all-reduces) in the transformer are:

- In the forward pass, to concatenate the model activations after the MLP block before adding dropout

- In the backwards pass, at the start of the self-attention block.

Now, I strongly suspect this is what GPT-3 and Jurassic-1 both did, but neither went into detail about the specific parallelism models they used, other than to say (from GPT-3):

To train the larger models without running out of memory, we use a mixture of model parallelism within each matrix multiply and model parallelism across the layers of the network.

Presumably, this style of parallelism is what is meant by “model parallelism within each matrix multiply,” as I find it hard to imagine what else they could mean.

Gopher

Gopher was a LLM trained by DeepMind. Interestingly, the lead author joined OpenAI shortly after it was published, along with a few of the coauthors. The architecture was the same as GPT-2, except:

- They use RMSNorm (instead of layernorm)

- Use relative positional encoding scheme from Transformer-XL (while GPT-* used a learned positional embedding)

- They use SentencePiece (instead of BPE). This seems to be an Alphabet thing; many of the Alphabet papers use SentencePiece, while most of the non-Alphabet world uses BPE.

The paper was very interesting from a computational perspective, as they went into detail about how they trained their model and made it work:

- They used optimizer state partitioning (ZeRO)

- Megatron-style model parallelism

- And rematerialization/gradient checkpointing to save memory.

These are all now the standard techniques used to train large models. To the best of my knowledge, Gopher was the first paper to put all of these together and release details about doing so publicly.

It’s interesting— often, big labs don’t include details for comeptitive reasons. Here, because DeepMind was (arguably) behind, they went into extensive detail. I think we’ll see this increase with LLM research from everyone that’s not OpenAI/Anthropic, as the others don’t live/die by the commercial success of their API, and have strong incentives to make it easier for **others** to train large models (and thereby commoditize their complements).

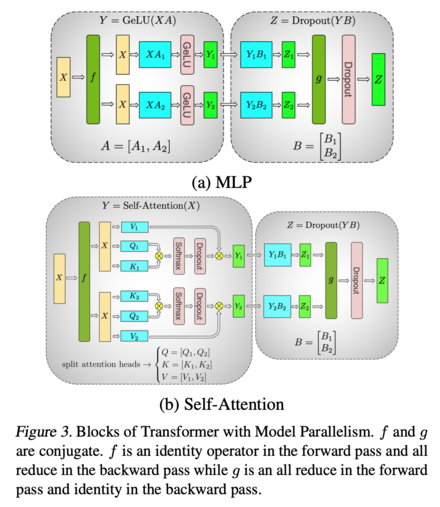

For the paper, DeepMind built a dataset called MassiveText, which was as follows:

Interestingly, this is much smaller than the dataset OpenAI used for GPT-3. GPT-3 had roughly 45TB of text, while MassiveText “only” had about 10.5TB.

They used this dataset to trained a large model on 300B tokens. The dataset consists of 2.343 trillion tokens, so this is only 12.8%. A much smaller subset. This is interesting to compare to the earlier GPTs, which, if you recall, used 100 epochs (so they saw each token in the dataset 100 times— while Gopher only saw 10% of their tokens once)!

The Gopher appendices have some great work; someone finally did ablations! They looked at:

- Adafactor vs Adam, and found that Adafactor was much less stable

- Lower-precision training, trying runs with float16, bfloat16, float32, RandRound, and using bfloat16 parameters with float32 in the optimiser state (rounding randomly). They found that using float32 parameters for optimisation updates only mitigated the performance loss, saving a substantial amount of memory.

- Scaling context length; they show how performance increases as the context length increases. Improvements see diminishing returns, but consistently improve. Performance looks roughly proportionate to \(\sqrt{n}\) (where \(n\) is the context length).

It’s really nice to see detailed empirical work like this— it’s a welcome change from the other papers that failed to do this.

Chinchilla

Chinchilla is an incredibly influential paper that established scaling laws. It’s one of my favorite papers from the last few years, as it actually does science in a way that physicists would agree with. One answer to “is something science” is to say, if you were to meet a historical scientist in your field, could you teach them something? And if you brought Chinchilla to researchers to, say, Radford et. al in 2017, it would advance their work by several years.

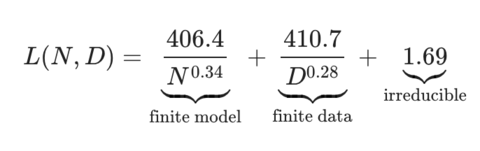

Chinchilla trained over 400 GPT-style transformers, ranging in size from 70M to 16B parameters, and fit the following equation (N is the number of parameters in the LM, and D is the number of tokens in the dataset):

\[\hat{L}(N, D) = E + \dfrac{A}{N^\alpha} + \dfrac{B}{D^\beta}\]Choosing \(A, B, E, \alpha, \beta\) to minimize

\[\sum \limits_{\text{Runs } i} \text{Huber}_{\delta=10^{-3}}(\log \hat{L}_i - \log L_i)\]where the Huber loss is

\[\text{Huber}_\delta(x) = \begin{cases} \frac 1 2 a^2 & |a| \leq \delta,\\ \delta \cdot (|a| - \frac 1 2 \delta) & |a| > \delta \end{cases}\]Here, we can think of E as the “irreducible loss” from the dataset, i.e. the loss if we trained an infinitely large model on an infinite stream of tokens. The authors find that the optimal model is (from nostalgebraist on into the implications of Chinchilla):

The implication here is that the model size & data size matter roughly equally, which is interesting, given how much attention & effort goes to scaling up the model, and how little attention is given to the dataset.

The authors then used this equation to determine the optimal model size for the Gopher compute budget, and trained it on more tokens— 1.4T tokens, 4.6x the number of tokens Gopher was trained on. This model, being 4x smaller, has a radically smaller memory footprint and is much faster/cheaper to sample from.

The Chinchilla paper has been highly influential. Almost every team that I’ve been talking to that is training a LLM right now talks about how they’re training a Chinchilla optimal model, which is remarkable given that basically everything in the LLM space changes every week.

The standard practice before Chinchilla was to train your model for 300B tokens, which is what GPT-3, Gopher, and Jurassic-1 all did. Chinchilla reveals how wasteful that was; basically, all of these papers made themselves more expensive to infer by training models that were too large.

Changes from Chinchilla (otherwise the same as Gopher):

- AdamW instead of Adam (there’s an interesting footnote regarding the choice of optimizer: “a model trained with AdamW only passes the training performance of a model trained with Adam around 80% of the way through the cosine cycle, though the ending performance is notably better”)

- Uses a modified SentencePiece tokenizer that is slightly different from Gopher (doesn’t apply NFKC normalisation)

- They compute the forward + backward pass in bfloat16, but store a float32 copy of the weights in the optimizer state. They find that this is basically identically efficient to using float32 everywhere.

All of the changes are ablated extensively in the appendix. None of these are particularly novel.

PaLM

Speaking of training models that were too large- we have PaLM! Palm was really, really big. As far as I’m aware, it’s the largest dense language model trained to date, at 540B parameters, requiring 6144 TPUs to train on (this is 3 entire TPU pods, each consisting of 2048 TPUs). This is incredibly expensive! Probably only Google has the resources + infrastructure to do this.

… unfortunately, they were training PaLM at the same time chinchilla was being written. Very suboptimal.

- Multi-query attention. Shares K/V embeddings for each head, but has separate Q embeddings. Makes it much faster during inference time.

- Uses parallel transformer blocks, which improves training time by 15%. As it was trained using 6144 TPU v4 chips for 1200 hours, the total training cost (at public prices) is between \(1.45 to\)3.22 per chip-hour, for a total of \(10M to\)22M. So this change saved \(1.5M to\)3M.

- SwiGLU activations, rather than the GELU activation used by GPT-3

- RoPE embeddings, rather than the learned embeddings

- Shares the input-output embeddings

- No bias vectors

- SentencePiece with 256k tokens

So, a ton of changes! Again, a bunch of these are common, e.g. using the learned embeddings that GPT-3 had is very passé, and almost no one does it now.

LLaMa

LLaMa combined a bunch of the best feartures from PaLM and Chinchilla:

- Pre-normalize the input of each transformer sub-layer

- RMSNorm, instead of LayerNorm, as done in Gopher

- SwiGLU activation function from PaLM (but a dimension of \(\frac{2}{3} 4d\) instead of \(4d\), as in PaLM)

- Uses rotary positional embeddings (RoPE) instead of the absolute positional embeddings, as done in PaLM

- Uses AdamW, as done in Chinchilla

I think that LLaMa is the recipe to follow for the current SOTA in training large models.

Computational changes:

- Uses efficient attention (Rabe & Staats, FlashAttention)

- Gradient checkpointing

- Interestingly, they appear to be using float32s everywhere (or at least, don’t say otherwise)

These are all similar to Gopher. The one obvious optimization they missed is to use lower precision, as Chinchilla did; I’m curious why they didn’t.

My one complaint is that I wish they would have trained the model for longer. The learning curve is very far from convergence! This paper is, in my mind, the shining example showing how well smaller models can do when trained well.

GPT-4

This is where I’d include information about GPT-4, if there was any. Unfortunately, the GPT-4 technical report contains almost no information:

GPT-4 is a Transformer-style model [33] pre-trained to predict the next token in a document, using both publicly available data (such as internet data) and data licensed from third-party providers. The model was then fine-tuned using Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) [34]. Given both the competitive landscape and the safety implications of large-scale models like GPT-4, this report contains no further details about the architecture (including model size), hardware, training compute, dataset construction, training method, or similar.

As a result, I’m not going to talk about it, as there’s not much to say. Hopefully OpenAI changes their mind and releases some information about their model.2

Conclusion

This is it, as of March ‘23. I’m sure something new will come along and invalidate all of this.

What have I missed? Add comments on Substack or email me and I’ll update it.

Articles I’m reading:

-

The paper itself doesn’t report the number of tokens, but OpenWebText, the open source reproduction, gets nine billion, using OpenAI’s tokenizer. ↩

-

To be clear, I highly doubt this will ever happen. ↩

Lately, I have been writing on my newsletter.