How is LLaMa.cpp possible?

If you want to read more of my writing, I have a Substack. Articles will be posted simultaneously to both places.

Note: This was written in March of '23, and is out of date (AI moves quickly!). This is an attempt at answering the question "How is it possible to run Llama on a single CPU?" and is not an attempt at documenting the current status of the Llama.cpp project. You should not rely on any of this post for specific details on how Llama.cpp functions.

Recently, a project rewrote the LLaMa inference code in raw C++. With some optimizations and quantizing the weights, this allows running a LLM locally on a wild variety of hardware:

- On a Pixel5, you can run the 7B parameter model at 1 tokens/s.

- On a M2 Macbook Pro, you can get ~16 tokens/s with the 7B parameter model

- You can even run the 7B model on a 4GB RAM Raspberry Pi, albeit at 0.1 tokens/s.

If you are like me, you saw this and thought: What? How is this possible? Don’t large models require expensive GPUs? I took my confusion and dove into the math surrounding inference requirements to understand the constraints we’re dealing with.

Let’s start with GPUs. GPUs have two main benefits for deep learning:

- They have a large amount of memory bandwidth (A100: 1935 GB/s, 4090: 1008 GB/s)

- They have a large amount of compute (A100: 312 TFLOPS of FP16, 4090: 82.6 TFLOPS of FP16)

When we talk about memory bandwidth, we’re talking about how long it takes to move things from the HBM memory (i.e. the RAM) into the on-chip memory. To actually do math with the GPU, we need to move the matrices in question into the on-chip memory, which is quite small (40MB on an A100, compared to 40-80GB of RAM). Note that the memory bandwidth is ~2 orders of magnitude smaller than the compute performance— this will matter later, as the memory bandwidth tends to be the bottleneck for inference.

What does this mean in the context of serving LLaMa? Let’s start with some inference arithmetic. We can do some rough calculations on the inference performance of a LLM using Kipply’s article1. First, some notation on the dimensions of the model:

- The \(Q\), \(K\), and \(V\) weight matrices are all shape [ \(d_{\text{model}}\), \(d_{\text{head}}\)], and we have \(n_{\text{heads}}\) of them per layer; the attention output matrix has the same shape, for a total of \(4 \times\) [ \(d_{\text{model}}\), \(n_{\text{heads}} \cdot d_{\text{head}}\)]. By convention, GPT-style networks have \(d_{\text{head}} \cdot n_{\text{heads}} = d_{\text{model}}\).

- The MLP has two weight matrices, of shape [ \(d_{\text{model}}\), \(4 \cdot d_{\text{model}}\)] and [ \(4\cdot d_{\text{model}}\), \(d_{\text{model}}\)]

- The embeddings matrix is of size [ \(d_{\text{vocab}}\), \(d_{\text{model}}\)].

This gives us a handy equation for the number of parameters in a GPT-style model:2

\[P = n_{\text{blocks}} \left( 4 \cdot d_{\text{model}}^2 + 2 \cdot 4 \cdot d_{\text{model}}^2\right) + n_{\text{vocab}} \cdot d_{\text{model}}\]For the duration of the post, I’m going to focus on the case where we’re running a ChatGPT style service locally, which is what LLaMa.cpp does, letting me assume a batch size of 1.

For efficient inference, the KV cache has to be stored in memory; the KV cache requires storing the KV values for every layer, which is equal to storing:

\[n_{\text{bytes}} \cdot 2 \cdot d_{\text{model}}\]I use \(n_{\text{bytes}}\) here to indicate the number of bytes per param; for float32s, this is 4, for float16s, this is 2, etc. The 2 in the middle is because we have to store one set of weights for the K values, and one for the Vs.

Given a model with n layers, the total memory for the KV cache is:

\[n_{\text{blocks}} \cdot n_{\text{bytes}} \cdot 2 \cdot d_{\text{model}}\]In addition to storing the KV cache in memory, we also need to store the weights themselves in memory; this requires \(n_{\text{bytes}} \cdot P\) bytes.

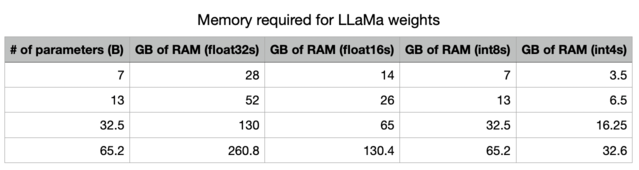

This is the advantage of quantization. By using less precision, we can radically decrease the amount of memory needed to store our models in memory. Note that, with int4 precision, all of these models fit into memory on an A100 (which is the standard datacenter GPU right now), and all of them, except for the biggest model, fit into memory on high-end consumer GPUs (3090s/4090s, which have 24GB of RAM).

It takes approximately \(2P\) FLOPS to run inference on our model for a single token, because we are doing a bunch of matmuls with a total of \(P\) parameters, and multiplying a matrix of size \((m, n)\) with a vector of size \((n,)\) has a cost of \(2mn\).3

With all that math out of the way, let’s calculate the requirements for running inference with LLaMa. The main requirements when it comes to sampling are:

- Keep the KV cache in memory, in addition to all the parameters.

- Read all the weights from HBM into the on-chip memory. Because we sample auto-regressively, we have to repeat this for each token we sample.

- Do the actual matmuls to calculate the output of our network.

The latency is the maximum of either the compute or the memory latency, as reading parameters into on-chip memory happens asynchronously in all modern tensor programming libraries. As a result, we write:

\[\begin{align*} \text{latency}_\text{model} &= \text{max}(\text{latency}_\text{compute}, \text{latency}_\text{memory})\\ \text{latency}_\text{memory} &= \dfrac{2 \cdot P \cdot n_{\text{bytes}}}{n_{\text{memory bandwidth}}},\\ \text{latency}_\text{compute} &= \dfrac{2 \cdot P \cdot B}{n_{\text{flops}}}, \end{align*}\]where \(B\) is the batch size. As \(n_{\text{memory bandwidth}} = 1.935e12\), and \(n_{\text{flops}} = 3.12e14,\) as long as the batch size is less than 161, the model is memory-bound.4

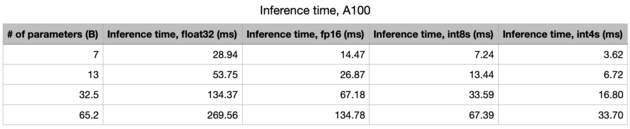

With a batch size of 1, this is the same equation, as on most hardware (e.g. Nvidia GPUs), there is a linear speedup as you decrease the precision (you get twice the FLOPS when using fp16 vs fp32, which doubles again as you go to int8, and doubles once more as you go to int4s).

As LLaMa.cpp uses int4s, the RAM requirements are reduced to 1.33GB of memory for the KV cache, and 16.25GB of VRAM for the model parameters. That’s pretty good!

As the memory bandwidth is almost always5 much smaller than the number of FLOPS, memory bandwidth is the binding constraint.

Running LLaMa on an A100

On an A100 (80GB PCIe), the memory bandwidth is 1935GB/s. The int4 compute is 1248 TOPS. As such, the model is (heavily) memory-bound. We should expect to see inferences as given in the table; roughly 30 tokens/s with the 65B model, and 277 tokens/s with the 7B model.

Running LLaMa on a M1 Macbook Air

The M1 GPU has a bandwidth of 68.25 GB/s, while the M1 GPU can do up to 5.5 TFLOPS of fp16 compute. As such, we should expect a ceiling of ~1 tokens/s for sampling from the 65B model with int4s, and 10 tokens/s with the 7B model.

As the M2 Pro has 200 GB/s of bandwidth, and the M2 Max has 400 GB/s of bandwidth, we should expect massive improvements with them, going up to 6 tokens/s with the M2 Max with the 65B model. That’s pretty darn good for a laptop.

Running LLaMa on a Raspberry Pi 4

A Raspberry Pi 4 has 13.5 GFLOPS of compute, and ~4GB/s of memory bandwidth. Given this, we’d expect to see ~2 tokens/s with the 7B model if it was memory bound. Given that we’re currently seeing ~0.1 tokens/s, I suspect we’re actually compute-bound (although this is a stab in the dark— I can’t find enough information about the specs for a Raspberry Pi to determine this with any precision).

Summary

Memory bandwidth is the limiting factor in almost everything to do with sampling from transformers. Anything that reduces the memory requirements for these models makes them much easier to serve— like quantization! This is yet another reason why distillation, or just training smaller models for longer, is really important.

Note: I’m not an expert in CUDA, so I probably have errors in my math. If so, please shoot me an email and let me know- I’d love to hear from you so I can learn more about how this works and update this post.

Resources on transformer inference performance:

- Large Transformer Model Inference Optimization

- Transformer inference arithmetic

- LLM parameter counting

- Efficient Transformers

Thank you to Kaushik Patnaik, Arthur Allshire, Stanislav Fort, and Tom McGrath for reading early drafts of this.

-

Almost all of this math is taken from their article; they deserve full credit. ↩

-

Although it’s an open question of how much Mac specific optimization is being done with LLaMa, or indeed, any of the tensor programming frameworks. ↩

-

For a more detailed discussion showing that this is the case, check out kipply’s article. ↩

-

If you’re following along with kipply’s post, there’s a slight discrepancy here, as I assume a 80GB A100 PCIe, which is what I see as the standard GPU. Their post assumes a 40GB A100 PCIe, which has slightly lower memory bandwidth. ↩

-

I hedge with “almost” here, but I’m not aware of any counterexamples. ↩

Lately, I have been writing on my newsletter.