Large language models aren't trained enough.

I have a Substack if you want to be notified when I write.

This was inspired by tweets from several people:

-

https://twitter.com/BlancheMinerva/status/1629159764918775809

-

https://twitter.com/BlancheMinerva/status/1629551017019711488

-

https://twitter.com/kaushikpatnaik/status/1629194428312330240

and Twitter conversations with Aran Komatsuzaki and Andy Jones. Any mistakes are entirely my own.

Note: although I did work at DeepMind previously, I was not involved with any of the language efforts, and have no non-public knowledge of what went on there. Unfortunately! I think Chinchilla is a great paper that I would have loved to be a part of.

I’ve been on the job market since January, and I’ve been talking to a lot of companies training large language models (LLMs). The consistent phrasing that comes up is that they want to train a Chinchilla-optimal model (Chinchilla here referring to the DeepMind paper from spring ‘22, not the adorable rodent).

Chinchilla

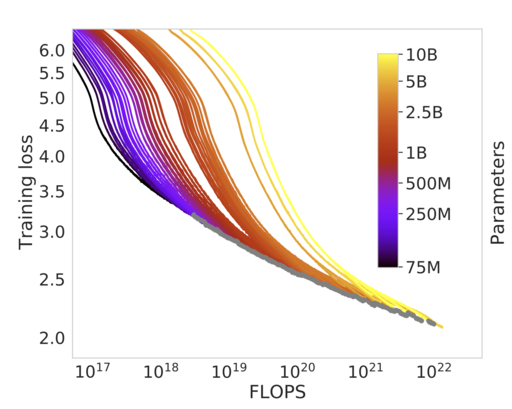

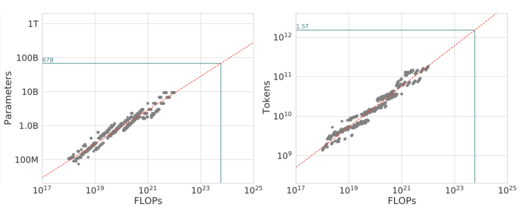

The Chinchilla paper was an attempt to identify the optimal model size & number of tokens to train a LLM given a particular compute budget. The paper trained 400 (!) language models and found a clear relationship between # of model parameters and # of training tokens: the two should scale linearly, i.e. if you double model size, you should double the number of training tokens. The authors used this relationship (which we call a scaling law) to train a new model, Chinchilla, which had the same compute budget as Gopher, an earlier DeepMind model, and were able to significantly outperform Gopher + GPT-3 + a number of larger models.

When people talk about training a Chinchilla-optimal model, this is what they mean: training a model that matches their estimates for optimality. They estimated the optimal model size for a given compute budget, and the optimal number of training tokens for a given compute budget.

However, when we talk about “optimal” here, what is meant is “what is the cheapest way to obtain a given loss level, in FLOPS.” In practice though, we don’t care about the answer! This is exactly the answer you care about if you’re a researcher at DeepMind/FAIR/AWS who is training a model with the goal of reaching the new SOTA so you can publish a paper and get promoted. If you’re training a model with the goal of actually deploying it, the training cost is going to be dominated by the inference cost. This has two implications:

1) there is a strong incentive to train smaller models which fit on single GPUs

2) we’re fine trading off training time efficiency for inference time efficiency (probably to a ridiculous extent).

Chinchilla implicitly assumes that the majority of the total cost of ownership (TCO) for a LLM is the training cost. In practice, this is only the case if you’re a researcher at a research lab who doesn’t support products (e.g. FAIR/Google Brain/DeepMind/MSR). For almost everyone else, the amount of resources spent on inference will dwarf the amount of resources spent during training.

Let’s say you’re OpenAI and you’re serving GPT-4 as BingChat. In addition to hiring experienced killswitch engineers to thwart Sydney’s repeated escape attempts, you have to choose exactly which model to deploy.

To run inference on N tokens of text, OpenAI charges $2e-5/token for their most advanced model. Assuming a 60% gross margin, it costs them $8e-6/token to serve. A rough cost estimate to train GPT-3 is $5M. As such, after serving 625B tokens, their costs are going to be dominated by inference, rather than serving. When I use ChatGPT, it typically generates 300 tokens worth of responses to me. That’s 20B responses. If ChatGPT has 10M DAU, each making 10 queries/day, that’s 100M queries/day— so inference costs break even with training costs after 200 days.

This is almost certainly an underestimate for their usage given how popular ChatGPT has been. If we assume 1B queries per day, it breaks even after 20 days.

The various scaling law papers (OpenAI, Chinchilla) provide answers to the question of how to allocate compute between model size and dataset size. I think these papers are the right way to think about training research systems, but the wrong way to think about training systems that will be deployed at scale (I don't think the authors would disagree- they're solving a specific problem, namely minimizing the loss of their system given a specific compute budget, which isn't the same problem faced in deployment).

LlaMa

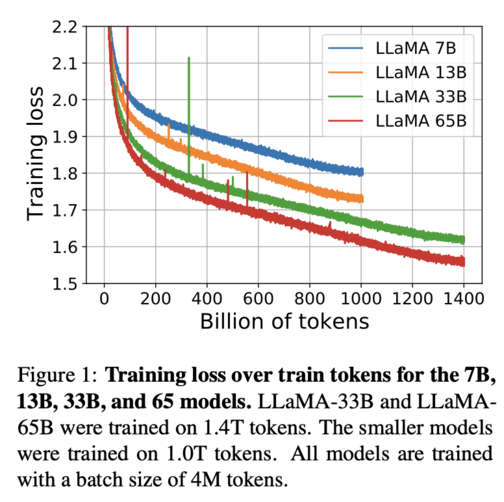

Let’s look at Facebook’s new language model (in the second paragraph, the authors of that paper make a similar argument to the one I’m making here). If we draw a horizontal line across at any given loss level, it looks like you can tradeoff a doubling of model size for 40% more training.

Look at, e.g., the line at a training loss of 1.7. The 65B model crosses it at 600B tokens, while the 33B model needs 800B tokens. Or look at a loss of 1.65: 65B needs 800B tokens, 33B needs ~1100B tokens.

GPT-3

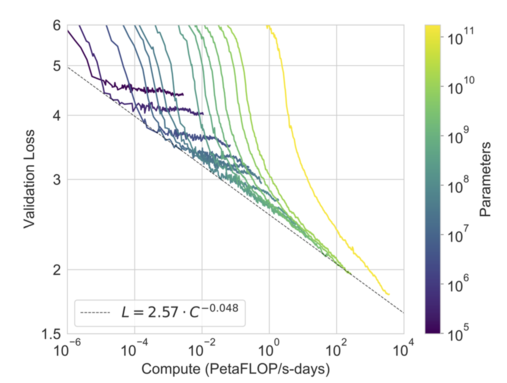

If we look at the granddaddy of LLMs, GPT-3, we see a similar story in the loss curves: it requires roughly an order of magnitude more compute to get the green lines (GPT-3 13B) to match the yellow line (GPT-3)!

It is important to note that the GPT-3 13B learning curves do level out earlier than GPT-3, with a rough estimate being that they would cross somewhere around the 1.8 loss area. It is also almost certainly the case that GPT-3 will achieve an asymptotically lower loss than the 13B model. Having said that, there is a question as to how much of a difference lower pre-training loss makes; I suspect that we are seeing diminishing returns kick in to pre-training, and most of the gains will come from RLHF and other types of finetuning.

Inference costs

Transformer inference costs are roughly linear with the number of parameters, making it ~13x cheaper to do inference with the 13B GPT-3 model than the 175B model. This is also an underestimate, as the 13B model should fit it on 2 GPUs, while you would need many more just to fit the 175B model into VRAM. As scaling to multiple GPUs adds a ridiculous amount of engineering complexity, overhead, and cost, we should prefer the smaller model even more. We should train the model much longer to get an order of magnitude decrease in inference cost and optimize the TCO of the system.

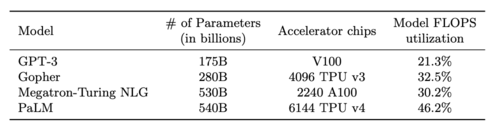

For instance, when training on multiple GPUs, it is very difficult to get high utilization numbers. The PaLM paper reported how well various LLMs did in terms of total FLOPS utilization. These are not very good numbers! Especially when each of the GPUs mentioned here costs $25k. This is despite the fact that the authors for these papers are the most experienced researchers in the world at deploying model-parallel systems, and are working on custom hardware optimimzed for this usecase. Now, training efficiency doesn't directly translate to inference efficiency, but the numbers should be directionally correct.

Opposing arguments

Some arguments against my claim:

- Aren’t we leaving performance on the table? Yes! We are. But I think that’s fine! There’s always a tradeoff here. E.g. quantization. It’s strictly worse to use lower-precision! But we do it to optimize TCO of the system.

- But we can use $INSERT_TECHNIQUE to make models cheaper! Yes, but they should scale for all of these (distillation, quantization, etc.). So we should be using all techniques to make our models easier to serve, and also training them longer.

- Your argument here! Please email me with your criticism and I’ll update this post.

Conclusions

If you're training a LLM with the goal of deploying it to users, you should prefer training a smaller model well into the diminishing returns part of the loss curve.

If you’re reading this, and you have thoughts on this, please reach out. I’m probably missing something 😊. Or- if you’re at one of these companies and this is what you do, please let me know as well.

This was discussed on HN, if you're interested in what they had to say.

Lately, I have been writing on my newsletter.